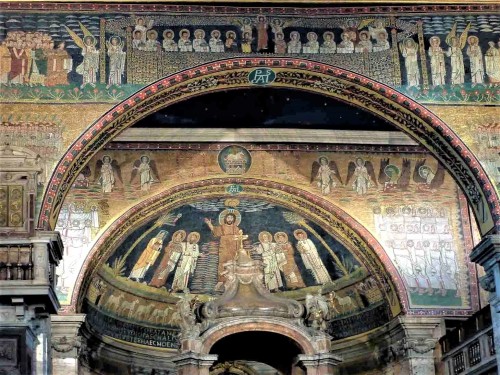

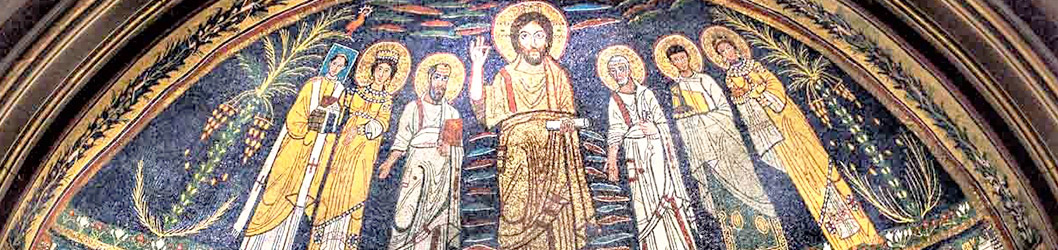

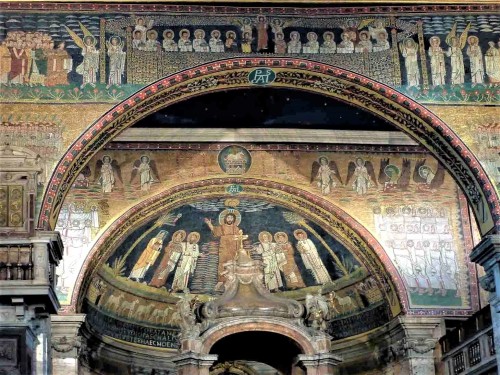

Church of Santa Prassede, mosaics funded by Pope Paschalis I

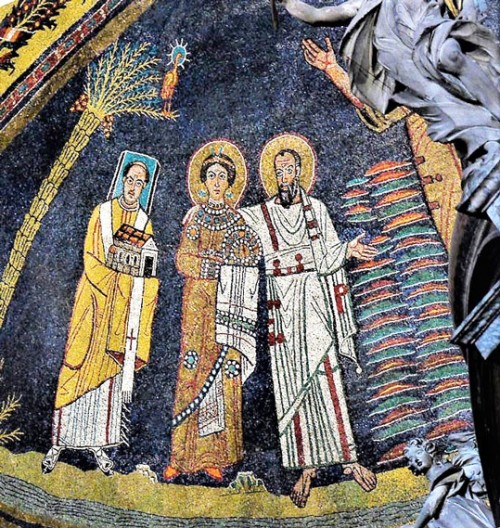

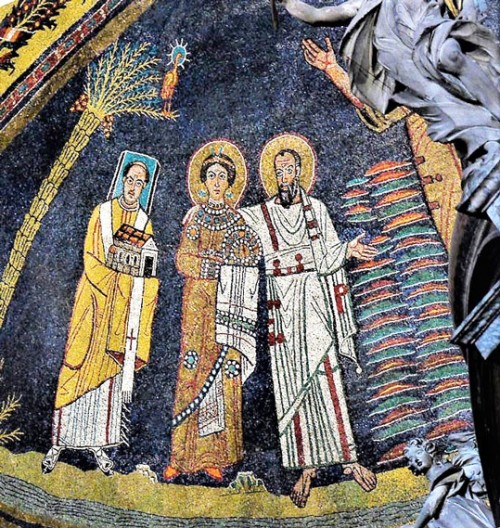

Church of Santa Prassede, mosaic in the apse, fragment, Pope Paschalis I with the model of the church

Church of Santa Prassede, mosaic in the apse, Pope Paschalis I with the model of the church

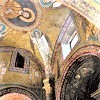

The San Zeno Chapel in the Church of Santa Prassede, foundation of Pope Paschalis I

Vault of the San Zeno Chapel in the Church of Santa Prassede, foundation of Pope Paschalis I

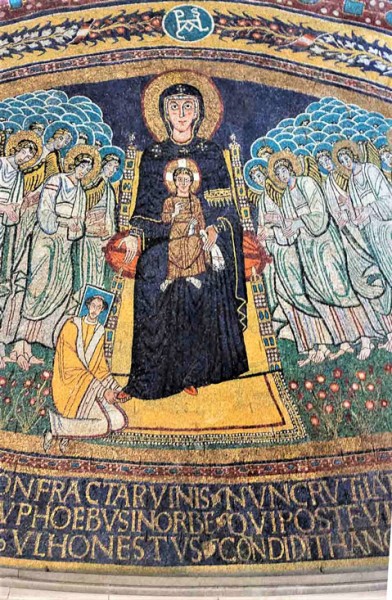

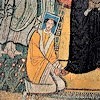

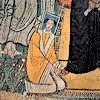

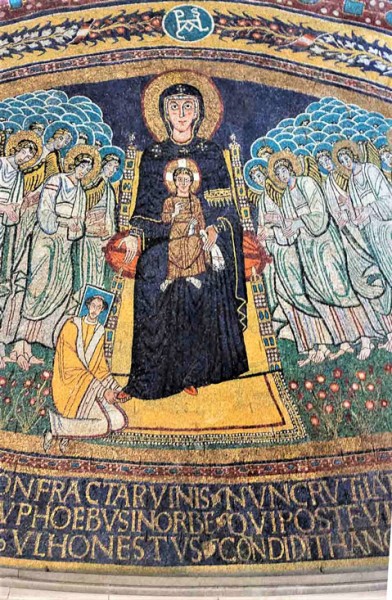

Pope Paschalis I, apse of the Church of Santa Maria in Domnica

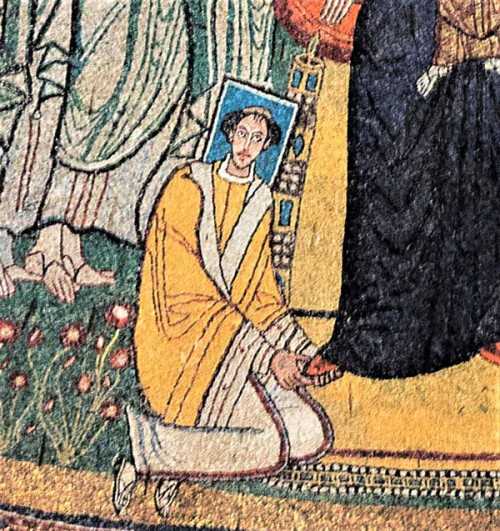

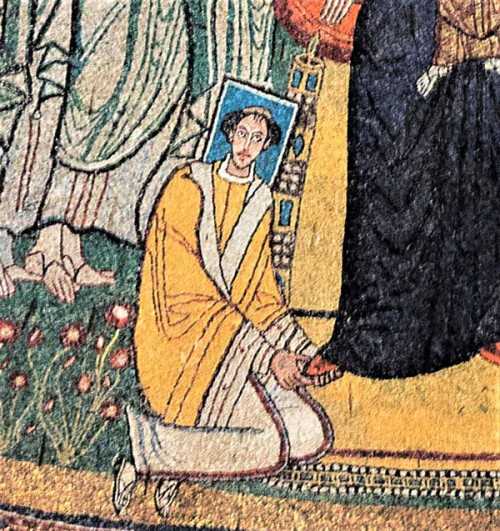

Kneeling Pope Paschalis I, apse of the Church of Santa Maria in Domnica

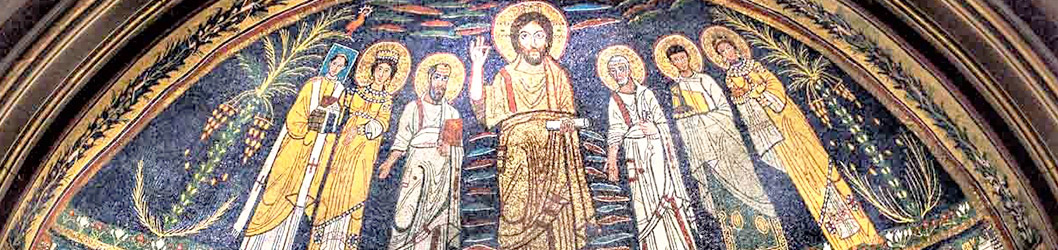

Apse of the Church of Santa Cecilia, Pope Paschalis I on the left

Apse of the Church of Santa Cecilia, Pope Paschalis I on the left

Despite the fact that he was only pope for seven years, he left behind imposing buildings, which he lavishly decorated and furnished with valuable gifts, but also numerous images of himself. Unheard of until then inclusion of the figure of pope among the saints in the decorations funded by him, proved his desire to accentuate the dominant role of the head of the Catholic Church in the political affairs of the time. But was that all?

Despite the fact that he was only pope for seven years, he left behind imposing buildings, which he lavishly decorated and furnished with valuable gifts, but also numerous images of himself. Unheard of until then inclusion of the figure of pope among the saints in the decorations funded by him, proved his desire to accentuate the dominant role of the head of the Catholic Church in the political affairs of the time. But was that all?

Initially Paschal was the abbot in St. Stephen’s monastery, found near St. Peter’s Basilica (San Pietro in Vaticano) and a collaborator of Pope Stephen IV. After his death (817), on the very same day he was elected as the bishop of Rome. His life, similarly to other popes, is known from the Liber Pontificalis, but also from Frankish sources, which – as opposed to an official Roman chronicle – paint a rather unfavorable picture of him, which should come as no surprise, taking into account that this was a period of increasing, although still heavily camouflaged mutual dislike of the king of Franks and the Roman emperor Louis the Pious and the pope. Paschal was also neither liked nor valued in the East, by the Emperor of the Byzantine Empire, Leo V. Truth be told he really did not care much for their sympathies – one of them he considered a puppet, while the other a relic of the past. His ambition was not to look for applause at the courts of either of the emperors, but rather to force the will of Rome upon them, while the means to achieve this goal was building the strong position of the papacy and independence of the State of the Church. It is hard to guess, how much of this was done with the good of the Church in mind and how much was simply personal pride. That he was not bereft of basic emotions can be testified to by how Paschal I had himself immortalized. To this end he used a very beneficial for himself moment of migration of craftsmen from the area of the Byzantine Empire, caused by the spread of iconoclasm. With open arms he welcomed them in Rome and ensured commissions at decorating churches which he funded. The mosaics completed by Greek masters, were however, different from those created in the Byzantine tradition, as they are characterized by a return to late-antiquity images of the times of Constantine the Great (IV century).

An idée fixe of Paschal was enriching churches and not only with material goods either. The practice of translation of corpses was known in Rome since the mid-VIII century, but Paschal turned it into a mass phenomenon. Catacombs around the city were virtually emptied of bodies. As the then chroniclers claimed, only in the Church of Santa Prassede, around 2300 corpses found their final resting place! Such a great proof of respect for martyrdom legitimized in a special way the place of Paschal I among all the bishops of the Christian world, giving him the right to be independent. For a man of the Middle Ages, concentrating on miracles and supernatural powers, the rank of a given place was explicitly connected with the presence of holy relics. They were the religious wealth, an invaluable treasure, but also a sign of prestige. During a bitter rivalry, especially between the pope and the Emperor of the Byzantine Empire, who exercised his right to sovereignty over Rome, Paschal could boast the appropriate amount of martyrs. This was important argument demonstrating his autonomous position and legitimizing sedes apostolica in Rome. Rome in such a dimension was a holy city, a land of martyrs and apostles – a second Jerusalem and a reflection of heavenly Jerusalem.

It is worth taking a look at the mosaics in the apse of the aforementioned Church of Santa Prassede, on which the pope was immortalized. On the right side of Christ stands St. Paul, putting his arm around St. Praxes, while next to them, on a square nimbus (used for those still living), is the founder, Paschal with a model of the church in his hand. On the palm which accompanies him, there is a sphinx, an Egyptian bird, the symbol of immortality. Paschal then calls as witnesses of his foundation Christ himself, the most important Roman apostles (SS. Peter and Paul) and the saint virgins (Pudenziana and Praxes). Interestingly enough his figure is nearly the same size as theirs, which means that the pope aspires to sainthood even in is life, while after death to eternal life, which is testified to by the phoenix above his head.

The Church of Santa Prassede was especially favored by Paschal I – he not only ordered it to be decorated with imposing mosaics; the Chapel of San Zeno was also created there, in which most likely the pope’s mother – Theodora (Episcopa) was laid to rest. Still today it is one of the leading examples of mosaic art of that time, a small jewel of Roman art. Even in Paschal’s time it was called hortus paradisi.

Another interesting portrait of the pope is found in the apse of the Church of Santa Maria in Domnica. Here he is kneeling at the feet of Our Lady, holding her slipper. However, this is not a gesture of homage and humility, but rather a demonstration of his close ties with the Mother of God, at whom the dignitary is not even looking, directing his gaze at us, as if awaiting applause. He will once again be seen in the apse of the Church of Santa Cecilia. Here, he is also holding a model of the church he founded, standing next to its patron St. Cecilia, who puts her arm around him protectively, with this gesture unequivocally valuing the greatness of his work and holiness of his persona, which is once again underlined by the sphinx which appears over the pope’s head.

The outstanding mosaics of which Paschal I was the founder, depict him in three different settings. This is a truly exceptional artistic document, the first such a manifestation of the greatness of the successor of St. Peter in Rome, but also marvelous, worthy of particular attention work of art, one of the most artistically attractive objects of the medieval period, that can be admired in Rome. According to chroniclers, Paschal ruled with an iron fist and his pontificate was marked with severity both towards the clergy as well as to laypersons. All instances of insubordination were brutally put down. Using all the means at his disposal, the pope eliminated his enemies, also in the literal sense of the word. He aroused such ire of the Romans themselves, that after his death street riots and even fights erupted between his sympathizers and opponents. The latter also did not allow for his burial in the Vatican Basilica. His body was laid to rest in the Church of Santa Prassede, which he had erected. It was only Paschal’s successor Eugene II, who ordered his body to be transferred to one of the Vatican chapels. However, it was not placed in the new basilica and ultimately was deemed as lost.

Structures created during the pontificate of Paschal I:

- Church of Santa Prassede with the mosaic decorations in the apse and in the triumphal arch, as well as the Chapel of San Zeno located there

- Church of Santa Maria in Domnica and apse mosaics

- Church of Santa Cecilia in the Trastevere and apse mosaics

- Enamelled reliquary in the form of a cross in a silver chest – furnishing St. Peter’s Basilica

- Mosaic decoration of the apse of the Church of San Stephano del Cacco (unpreserved)